invited to drive the one and only LT2 Jaguar XK120 at Le Mans.

In the summer of 1950, after watching three alloy 120s race well at Le Mans, Lofty England and Bill Heynes both came to believe that Jaguar could win the 24-hour race. After some convincing, William Lyons authorized designers and fabricators at Browns Lane began work on what became known as the C-Type. However, by early winter of 1951, William Lyons concluded that the Experimental Department’s construction efforts were behind schedule. To ensure Jaguar was represented at Le Mans, Lyons ordered the preparation of three lightweight XK120 race cars. They would be held in reserve, and if the C-Types failed to be ready for the approaching June race, the Lightweights would be entered. Metal men at Abbey Panels, using English wheels, gas welding, and hammer and dolly, created three incomparably beautiful magnesium alloy bodies to enclose race-prepared XK120 chassis and engines. These one-off bodies duplicated the gorgeous lines of the XK120, but unlike the 120, they were fabricated out of what appeared to be a single piece of magnesium alloy. There were no joining surfaces between the rear wings and the body, nor the bonnet and the front wings. The bonnet was now an easily removed louvred panel, just above the engine. The first body was never used, but the second and third bodies became the reserve race cars for Le Mans in 1951. Jaguar designated them LT2 and LT3. These two cars remain today the rarest of all Jaguars in private hands. LT2 is in the collection of Club member Chris Jaques, and is the only one of the two that continues to do what it was intended to do…race.

Late last year I received a call from Chris. It was during the Christmas holidays and I thought it was a message of good cheer. It was indeed a holiday greeting, but as the conversation concluded, Chris casually mentioned that he was thinking of taking LT2 to the Le Mans Legend race in June of 2013 and asked if I would be interested in sharing the car with his regular driver, Rob Newall. It was an incredibly generous offer and it did not take long to indicate that I would love to join the effort. Rob is a superb driver who has raced Chris’s cars for years, instructs at Silverstone for Porsche, and has had hours of experience and great success at Le Mans in LT2. On the other hand, I had never raced LT2, never raced a right-hand drive car, and had never seen the Le Mans circuit. As a Californian, there was no chance to race LT2 in advance, and there was no chance to drive a right-hand drive car, but a type of track experience at Le Mans could be obtained, if unconventionally. During the winter and spring of 2013, I watched hours of cockpit video of vintage cars racing at Le Mans. Although intended as entertainment, and possessing varying degrees of usefulness, if watched carefully, these videos allow one to learn the 8.5 miles of race track, particularly the succession of turns, lines through corners, and a close approximation of brake points.

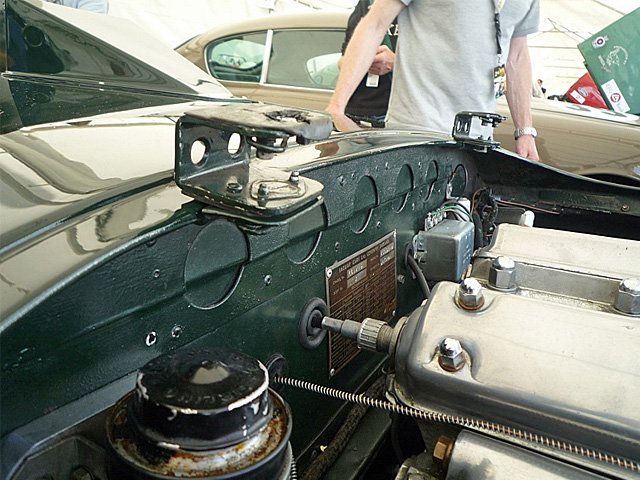

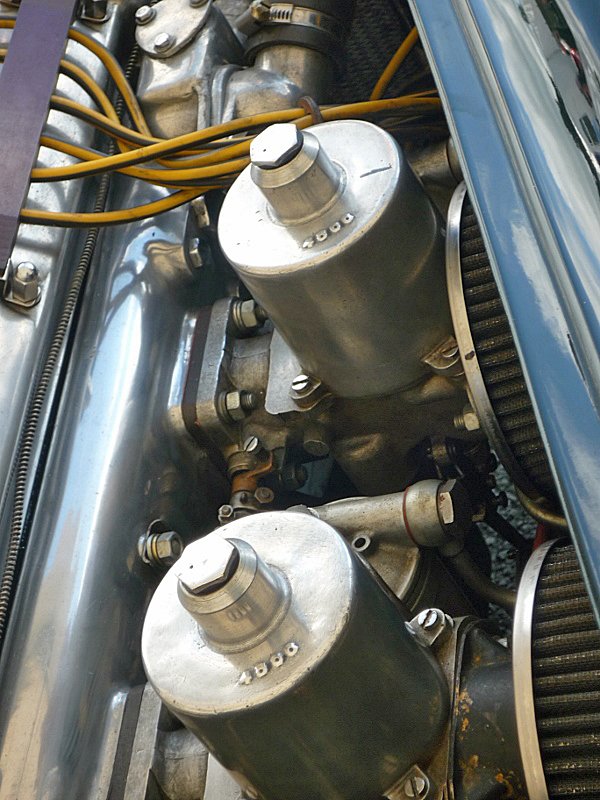

I arrived in England four days in advance of the June 22 race to help in the final work to ready LT2. Chris’s preparation of his race cars for competition is meticulous. All major tasks had been accomplished before I arrived. The front ride height had been brought back to original. LT2’s original self-adjusting brakes, that were not available to the public in 1951, were completely rebuilt. Rally cams had been removed and racing cams were reinstalled. LT2 has its original ENV rear axle, with the nearly impossible to find ring and pinion gears. Over the years, Chris had assembled a set of these gears in different ratios, and the final job was to install the “Le Mans long ratio.” It was a 3.29, and would allow us to take full advantage of the long straights. We were ready to go.

We arrived at the track on the Wednesday afternoon before the race to participate in tech inspection. The Le Mans Legend race is the most prestigious of the vintage race events at the Circuit de la Sarthe. Duncan Wiltshire, who directs the Legend race, puts on an extraordinarily well organised event. As a result, we sailed through the inspection process and headed for our headquarters. Chris had arranged our accommodations at a large, quiet, and beautiful farm house about ten miles from the circuit. He knew that here, under one roof, we could make and adjust our final race preparations. A one-hour practice to set the race grid was scheduled for Thursday afternoon. The day dawned cool, clear, and perfect for racing. Chris had worked out a plan for practice that would simultaneously get us a good starting position, and also give me as much track time as possible. The idea was that Rob would go out first and do three 8.5 mile laps, a lap to get him settled, a fast lap for our grid position, and an in lap. We were the second oldest car in the race, but Rob worked his magic and put us well up the grid in a field of sixty-two cars. As we stood on the pit wall watching Rob’s practice laps, John Watkins, our mechanic, must have read the tension in my face. He turned to me and in his naturally calm voice, said that no one on the team expected me to be as fast as Rob, and that I should start well within myself and only slowly bring down the lap times. It settled me down immediately. Rob came in, I jumped in the seat and as John was buckling me in, Rob knocked on my helmet and reminded me of the speeds of the Mulsanne and the drum brakes. It was fortuitous.

I got on the track, but immediately carried too much speed into the Dunlap Chicane. The new front suspension setup got me through and I did a little better on the slightly downhill S-bends and short straight leading into Tertre Rouge. Tertre Rouge is a joy in LT2. It is a smooth right-hand bend where you can come fully on to the power just before the apex. Good exit speed here is crucial as it allows you to use the potential speed of the first of three sections of the Mulsanne straight. The Mulsanne is a two-way main road at all other times of the year, and thus has a distinct crown in the middle. With LT2’s original recirculating ball steering system, you must stay away from that crown, using one side of the road or the other. If you find yourself in the middle, the car will hunt, and hunt unpredictably. At Mulsanne speeds, it only took one experience to fix the mistake.

I had been racing regularly during the late winter and early spring, but there was no circuit in California that prepared me for the speeds of the Mulsanne. With Rob’s minutes-old advice in mind and the tach reading a little over 6,000, I braked for the first chicane far earlier than planned, and with the drums protesting mightily, only just got LT2 set up and then through. With adrenaline in full flow, it was back on the throttle with the engine pulling beautifully down the second section of the Mulsanne headed for the last chicane, which I came through a little more elegantly. The third and final section of the straight leads to Mulsanne Corner. It is a ninety-degree right-hand turn, and with our rear axle ratio it could to be taken in second gear. (Here, in 1955, Mike Hawthorne’s D-Type, with a 2.9 rear axle ratio, consistently used first gear.) Approaching the corner, LT2 pulled down straight as an arrow. I went down to third and then second gear, and began to feel as if I was coming to grips with the brakes and the speeds. Chris maintains his race cars in absolutely original condition, and in regard to LT2, this means he does not use a limited slip differential. Having long since forgotten this, at the apex of Mulsanne Corner I put in the power as if it was a limited slip, only to find the engine at high revs, but LT2 going nowhere. The spinning inside rear tire ultimately hooked up, but I only understood what had happened halfway down the ensuing straight to Indianapolis Corner.

When speed at Le Mans is talked about, this section between Mulsanne Corner and Indianapolis is never mentioned, but this part of the course is every bit as fast as any portion of the Mulsanne. You approach Indianapolis blind, then as you come over a rise, a ninety-degree banked left hander can be seen. Chris had told me, from his own experience racing LT2 at Le Mans, that even with the drum brakes you could stay on the power over this rise and down toward the turn. He was absolutely right. Indianapolis is a second-gear, ninety-degree left-hand turn, and with Mulsanne Corner in mind, I fed in the power far more carefully and got through nicely on the banking. Second gear can be carried down the short chute to Arnage, the last ninety-degree turn on the track. Another gentle application of power and you are on to a straight that leads to what became my favourite part of the circuit, the Porsche Curves. The Curves are a series of smooth, newly surfaced, sweeping S bends. They were absolutely made for our XKs. Lifting slightly as you approached each one, you could hold on to the power through the entire bend. With the original rear axle, LT2 could not be steered with the throttle through these bends, but I found that the natural tendency of the light rear end to step out just a bit could be used to bring the car through these curves with a great sense of accomplishment. After the Porsche Curves there is a short straight, with the pit entrance on your right. At this point you must be aware that up ahead looms the compact Ford Chicanes. You come on to them at speed without any visual cues to help you; they simply must be anticipated. You come through here in second gear, and if you slightly run the raised area on the track side of the two rumble strips, you can carry that extra speed onto the pit straight.

Utterly exhausted, I nevertheless had one lap of Le Mans experience in hand. In the succeeding four laps, I slowly relaxed, energy came back some, and lap times went steadily down. On the Mulsanne during these laps, LT2 tracked most comfortably at speed on the left side. Here I could take long breaths, check the gauges, and enjoy the extraordinary quickness of the car. On what turned out to be the last practice lap, LT2 came down the long straight to Indianapolis holding speed over the rise and down toward the left hander. I set the car up on the right, went down to third, and then in the shift to second, the toe of my shoe slipped off the brake and before I could catch it, tapped the throttle. That was enough, there was too much speed, the car came around and the rear tires slid off into the trap. Although LT2 and I were fine, and we got back on the track in good order, the same could not be said for Chris, John, and Rob. I knew immediately what would be happening on the pit wall when LT2 did not appear. With stopwatch in hand, looking hard at the Ford Chicane, every imaginable thought would be going through their minds. As it turned out, it was the last lap of practice and we were all flagged off to our paddock where I arrived before anyone. When the three of them came through the paddock entrance, there was much relief and lots of questions. I had worked diligently during the winter and spring on fitness, but in retrospect the mistake was rooted in an exhaustion that is difficult to prepare for; exhaustion produced by anxiety. It had resulted in decreased concentration, and resultant clumsy footwork.

Friday, the day after practice, was a free day that John and I spent leisurely talking while he prepared the car. He disassembled and checked the drums, cleared the rubble from the off at Indianapolis (at which time I bore the full force of English humour), and generally got the car presentable for Saturday’s race.

Rob Newall is a racer. He does not simply want to do fast lap times. His idea of racing, and what he is so good at, is competing with the car in front of him. With this idea in mind, Chris put together our race plan. The race would begin with what I was familiar with in California, a rolling start. I would thus go out first, do three laps, and Rob would finish the race working his way up through the field. At the end, Chris turned to me and asked if I would need a signal from the pit wall on when to come in. Foolishly, I said no.

Race morning began with intermittent rain, which continued with varying intensities for our entire race. On the 8.5 mile pace lap, some parts of the course had running water while other parts were dry; however, when the green flag dropped it was raining steadily, and as it turned out, everywhere. My entire race experience had been in the western United States, and while I had gone out on tracks where it had recently rained, I had literally never raced in the rain. It was an instructive experience. The English complain about their weather, but it has produced some of the greatest drivers of the 20th and 21st Centuries. If you can race well in the wet, you can run comfortably on the edge of adhesion in the dry. I drove within myself, initially slowing for umbrellas that signaled the periodic heavier bursts of rain. To English racers, this is perfectly rational, but to me it was counter intuitive; the more it rained the better LT2 gripped. The track, of course, was being washed clean of oil and dust and although I could not immediately understand what was happening, there was no denying the better grip. By the end of my stint in the rain, I could amazingly bring LT2 through Tertre Rouge and the Porsche Curves at speed with a real degree of control.

Although I did not know it, by the third lap, I had hopelessly lost count. In the middle of this lap LT2 crested the rise into Indianapolis only to see in the distance the roof of a red Aston Martin DB2. Later I learned that the car had slid sideways at speed into the runoff, and as it slowed, the wheels went deep into the gravel and rolled the car over. The driver was uninjured, but the beautiful alloy body was heavily damaged. Thinking that I was finishing my second lap, rather than my third, I ran right past the pit entrance. In blissful ignorance, I came in on the fourth lap, mistakenly pleased with myself for holding up my end of the partnership. Even among English racers, Rob is extraordinary in the rain. He brought us up through the field, but it was far less than he could have done if he had another 8.5 miles of track to work with.

That evening we all gathered at a lovely restaurant to celebrate. We all had experienced the race in different ways. It was easy to sense that Chris was well pleased. He had organised our entire effort, prepared the car in every detail, had passed along key track advice, and established our racing strategy. John had kept us running, and brought calm to the group, particularly to me. Like all of his race driving, Rob had brought not only speed to our effort, but speed that did not destroy components. A little over 50 years ago, Lofty England said that there were two kinds of drivers: ones who could go fast but were “rough handlers,” and ones that could go fast with a light touch. He would have been well pleased with Rob. For me, an historian by profession, the experience centered on driving one of the most historic, rare, and original Jaguar racing cars, the incomparably beautiful LT2.

Check out all the photos from the 2013 Le Mans Legend.